by T. M. Bradshaw

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the January 2025 issue of the Catskill Mountain Region Guide. Issues of the magazine are available online at issuu.com. Search for the magazine by name at that website. Thanks to John More (471721) for finding this article by chance and sending us the magazine in the mail. Thanks to T.M. Bradshaw and the magazine for graciously allowing us to use the article.

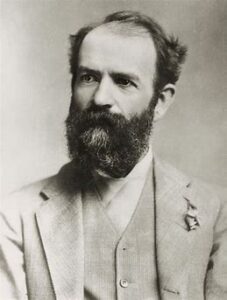

Jason Gould was born on a 150-acre dairy farm in Roxbury on May 27, 1836. If the name seems familiar, but not quite right, it’s because you know him as Jay Gould. From his early life it was clear that he wanted to steer his own course and would do what he needed to make it happen.

He was the long-awaited son of John Burr Gould and his wife Mary More, who had five daughters already. John Gould was eager for sons to help with the work on the farm, which was described as nonproductive. But Jay was small and sickly and as he grew, showed no interest in farming.

A rapid succession of deaths plagued the family—Mary died in January 1841, months before Jay was five. John remarried that summer, only to lose his new wife, Eliza, in December. Wife number three, Mary Ann Corbin, joined the family in the spring of 1842. Daughter Nancy died later that year. Another son, Abraham, arrived in March of 1843. When Mary Ann died in 1845 the Gould daughters took over care of their two little brothers.

The family’s farm was not owned, but leased from the Hardenbergh Patent, part of a feudalistic system of enormous land grants to individuals who received rent from the people who actually lived on and worked the land. An anti-rent movement developed, which John Gould viewed as insurrection; frequent skirmishes flared between John Gould and his neighbors.

In the spring of 1849, thirteen-year-old Jay, uninspired at the local school, wanted to attend the Hobart Academy. His father eventually relented. Jay boarded with a blacksmith in Hobart while attending the academy, earning his keep by keeping the blacksmith’s books. He walked home on weekends to visit the family.

After six months in Hobart, Jay returned home when a new teacher was hired at his old Roxbury school. With Jay having no interest in farm work, with Abraham too young to be of much help, with daughters either married or planning on doing so, John Gould decided a better option would be to make use of Jay’s natural inclinations toward more intellectual pursuits and made arrangements to swap the farm for Hamilton Burhan’s tin and stove business in town. Prior to the actual exchange of properties, Jay was sent to live with the Burhans to learn the business. He was by this time finished with the local school, but pursued his own educational interests in mathematics, engineering, and surveying.

The tin business didn’t appeal to Jay either—he was more interested in exploring new places. He secured a job with a surveyor named Snyder who was planning on mapping Ulster County. In April 1852, shortly before his sixteenth birthday, Jay took off on his new career. He soon found that Snyder’s instruction to note daily expenses—room and board at farms—in an account book for Snyder to settle later wouldn’t work, as the area farmers didn’t trust Snyder to pay. But then someone paid Jay to mark a line that the sun would strike at noon to facilitate setting the clocks. He began paying his own expenses from the money earned marking these noon lines for others.

Snyder did prove to be bankrupt, not a first time experience for him. Since he couldn’t pay Jay and the other surveyor, Peter Brink, they took instead the rights to his map. After adding a third surveyor, Oliver Tillson, the three young men completed the job. Jay’s share from the work was $500.

Next came a job in Albany, surveying for a plank road while attending Albany Academy. Then an entrepreneurial leap—he sought subscriptions for a survey and map of Albany County, followed by one for Delaware County. He would also compile a history of Delaware County. He wrote to Colonel Zadock Pratt, asking if Pratt would commission a map of Greene County. Pratt declined but promised to keep Jay in mind.

For the Delaware County project, Jay, now seventeen, sometimes boarded with Simon B. Champion, a young man who had started a newspaper, The Bloomville Mirror, in 1851. Champion taught him to set type. At some point Jay contributed five dollars to help expand readership of the Mirror. Now he asked Champion to campaign on behalf of the Delaware County map.

“In Delaware County the Supervisors ought to encourage it (the map) by buying maps for each of the school Districts, . . . I want you to give me an editorial to this effect . . . and for every farmer to have in his home, for every merchant and lawyer’s office . . .it must be as strong as it can be made and come direct from you.”

Jay had previously had dreams of attending college, Yale and Harvard were two he considered interesting possibilities. But at about this time he decided that what he really wanted was to be rich and that further formal education wasn’t necessary to reach that goal, life itself would provide the required lessons.

Gould and Pratt reconnected in 1856, Pratt hiring Jay to survey his farm and to write speeches and important letters for him, paying him very well for his efforts. Pratt had closed his Prattsville tannery, having depleted the available hemlock necessary for the process. Gould suggested Pennsylvania as a prime location for a new tannery—plenty of hemlock and the new Delaware & Lackawanna Railroad a means of bringing in pelts and shipping out finished product. Their partnership was based on Pratt’s money ($120,000) and Gould’s energy, surveying experience, and day-to-day management of the project.

The settlement supporting the new tannery was soon named Gouldsboro. Pratt came to believe that his share of the profits was short and that Gould was embezzling. Gould borrowed $60,000 to buy Pratt out.

Years later, just after Gould’s death, the Delaware County Dairyman of December 16, 1892 commented on the Pratt-Gould business relationship by relating a story from the Roxbury Times. In it, it was noted that initially Pratt had the money and Gould the [surveying] experience and “when they parted, Jay had both.”

During the Panic of 1857, which became an international financial crisis, Gould acquired a majority of the stock of the Rutland and Washington Railroad in Vermont for ten cents on the dollar. That was the start of a pattern of speculation and questionable business practices involving railroad acquisitions, political lobbying, involvement with Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed, and an attempt to corner the gold market that led to 1869’s Black Friday and months of economic turmoil that bankrupted farmers as well as Wall Street firms.

Throughout his lifetime newspapers and their cartoonists frequently skewered Gould, but there continued to be some who sang his praises, generally after receiving funds from him. Much of this was rehashed after his death on December 2, 1892. The Stamford Mirror (Champion had moved it from Bloomville in 1872) noted on December 20, 1892, “Rich people, generally, were Jay Gould’s victims, and those who were in the same business he was. He didn’t make his fortune by skinning the poor.” Another item in the same edition picked up an item from a Kansas paper:

St. John Speaks Well of Gould

Topeka, Kan., Dec. 14.—Ex.-Gov. J. P. St. John writes the following to a Kansas newspaper:

“In the midst of all that is being published against Jay Gould please allow me space to say that in 1880, when settlers in Western Kansas were penniless and were threatened with starvation, I wrote to this much-abused man about it. He promptly sent me $5,000 which was invested in bread and meat for their relief.”

But most coverage after his death was more like what James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald wrote, “He exercised a large influence over the careers of many who had commercial aspirations. That influence tended to lower the moral tone of business transactions. The example he set is a dangerous one to follow. The methods he adopted are to be avoided. His financial success, judged by the means by which it was attained, is not to be envied. His great wealth was purchased at too high a price. He played the game of life for keeps, and he regarded the possible ruin of thousands as a matter in which he had no concern.”

Shortly before his death, Gould promised significant financial support for a community project in his hometown of Roxbury. The Reformed Church had lost three buildings—two to high winds in 1867 and the third to fire in 1891. Gould agreed to contribute if the replacement would be made of stone. He died before being able to see the project through, but his children did. The new building was dedicated in 1894 as the Jay Gould Memorial Church.

T. M. Bradshaw shares other thoughts on history at tmbradshawbooks.com.